Everlyne Khasoa holds her three-month-old son

close, his tiny fingers curled around hers.

She has done everything right, attended prenatal

checkups, taken her medication religiously, and followed every instruction

doctors gave her.

Yet for months now she battles a relentless

anxiety—the fear of running out of antiretroviral drugs that are her son’s

lifeline. For the past few months, the dispensary where she collects

life-saving antiretroviral (ARV) drugs for her baby has faced severe shortages.

She recalls the last time she left the clinic

with barely enough to cover their monthly dose.

“I felt helpless,” she says, her voice breaking.

“What kind of mother cannot protect her child?”

Everlyne was diagnosed with HIV five years ago.

She was assured that with strict adherence to

treatment, her child could be born HIV-negative.

For

nearly two years, her viral load has remained suppressed.

But the recurring stockouts of essential drugs,

especially zidovudine syrup, crucial in preventing mother-to-child

transmission, have left her in a terrifying predicament.

“I have had to ration my baby’s medicine,

knowing the risk,” she says. “It’s terrifying.”

And she is not alone. Across Kenya, thousands of

mothers living with HIV face the same uncertainty. What happens when

life-saving drugs are simply unavailable?

Deadly impact of stockouts

At a government clinic in Kakamega, Samuel

Mujera, a clinical officer specialising in HIV treatment, explains the grim

situation.

He has seen firsthand how stockouts erode years

of progress.

“Yes, we’ve had multiple shortages this year,”

he confirms. “Zidovudine syrup has been unavailable for almost a year, and

septrin syrup, which protects against opportunistic infections, has been

missing for three months.”

Mujera also mentioned a shortage of atazanavir

tablets, which are important for adults on second-line HIV treatment.

Atazanavir is effective when the first-line

treatment fails because the virus does not easily develop resistance to it.

“Between July and August last year, atazanavir

stock ran out,” he explained. “We had to ration the limited supplies available

while waiting for replenishments.”

Without these medications, the risk of HIV

transmission through breastfeeding increases significantly.

“We are left hoping that a single drug will be

enough,” Mr. Mujera admits. “But when a baby tests HIV-positive simply because

we lacked all the necessary drugs, it’s devastating.”

Many mothers, like Everlyne, are forced to travel long distances in search of alternative health facilities. Others, especially those in remote areas, have no choice but to wait and hope.

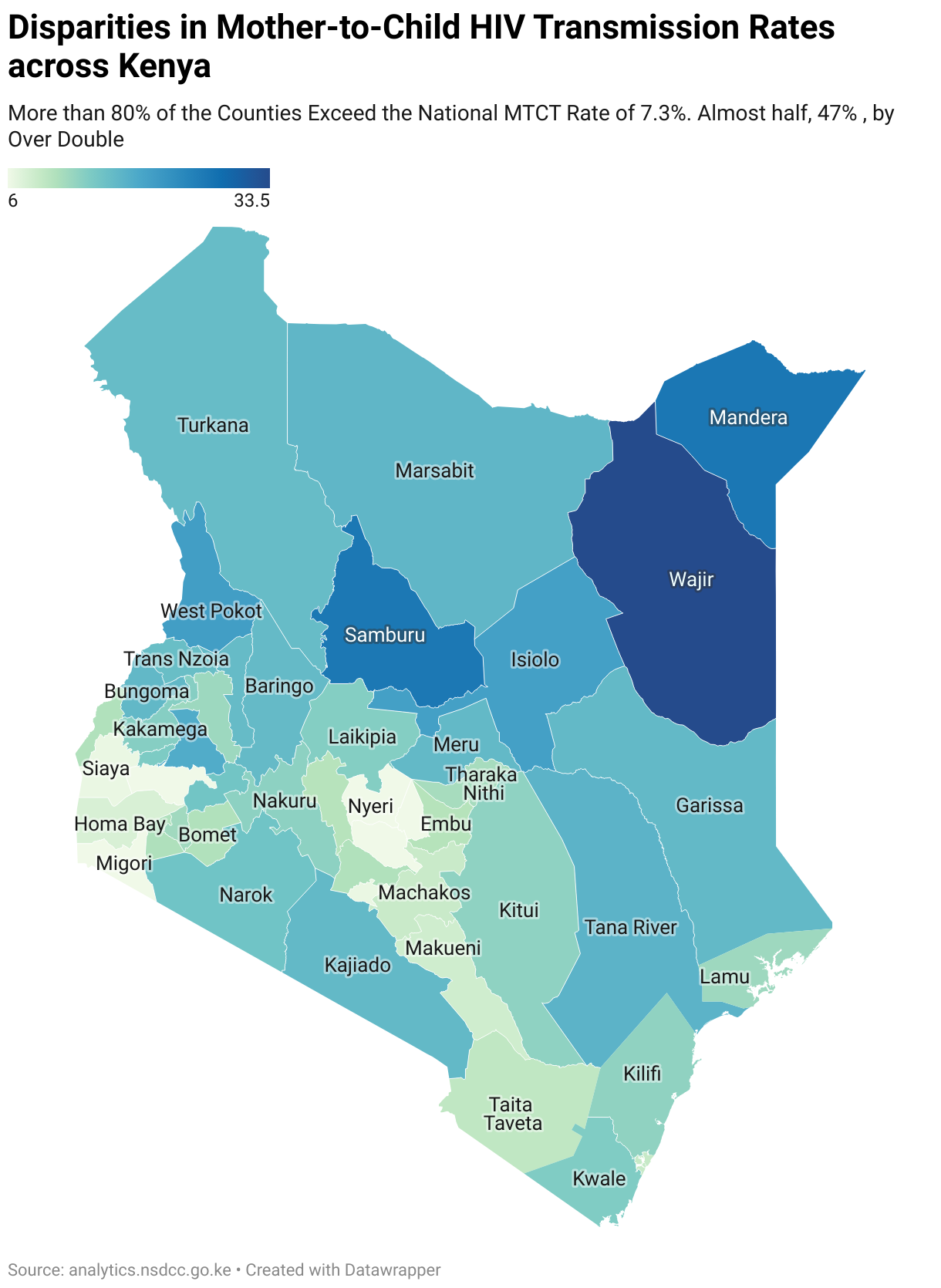

Kenya’s target is to reduce mother-to-child HIV

transmission below 5%, yet some counties, like Kakamega, still report rates as

high as 10-14%. The situation is dire.

Why these drugs matter

Dr. Joseph Maina, a research scientist at the

Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI), explains why these particular

medications are so critical.

“There are three critical stages when

transmission is most likely to occur: during pregnancy, delivery, and

breastfeeding.

“In the uterus, the likelihood of transmission

is relatively low, between 15-30% without intervention,” he said. “However,

complications like severe trauma or infections can allow the virus to cross the

placenta.”

During delivery, the risk increases due to the

potential mixing of maternal and neonatal blood.

Breastfeeding presents another risk, as HIV can

be transmitted through breast milk, especially in the early months when an

infant's immune system is immature.

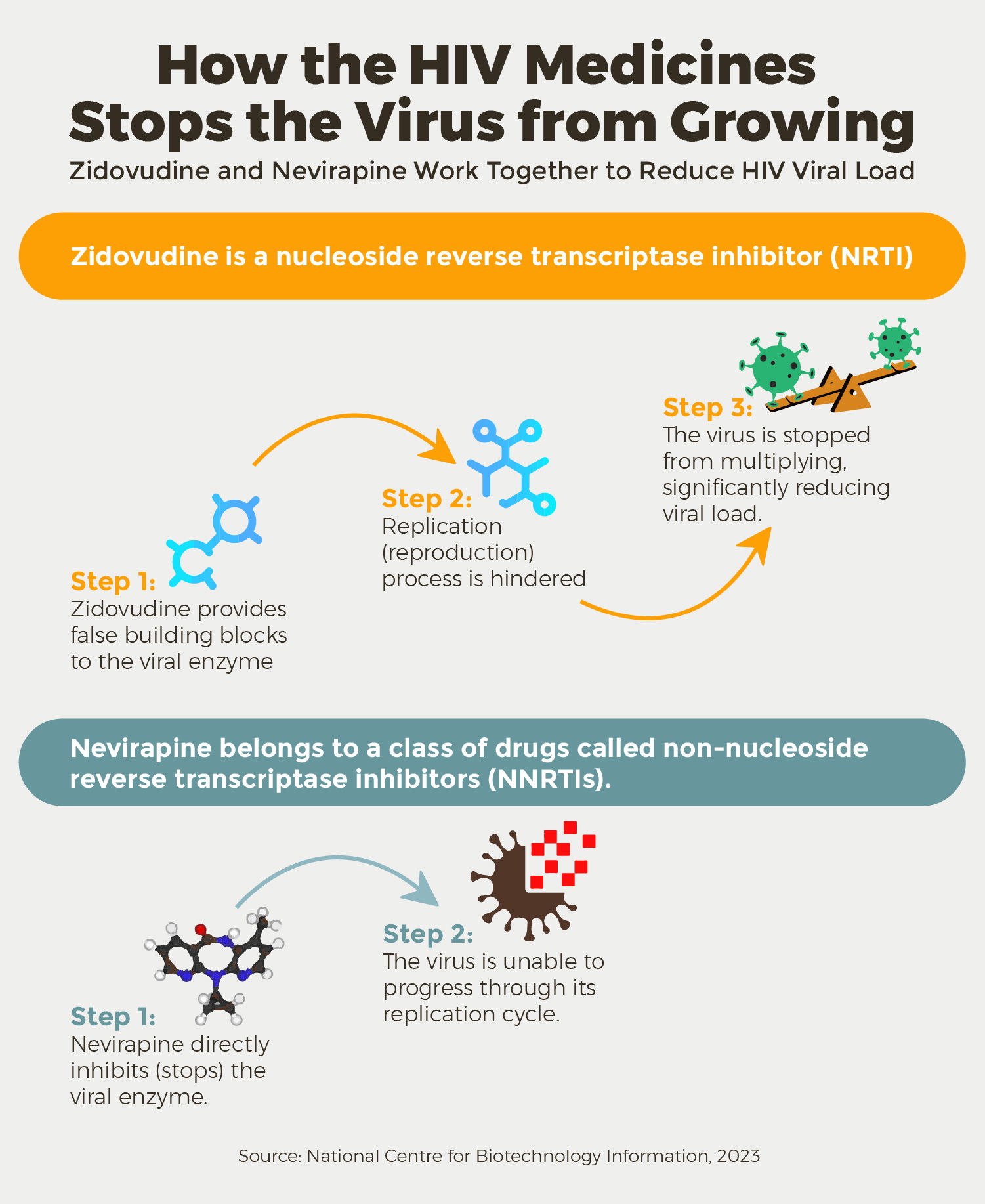

“These drugs work at different stages of

the virus’s life cycle. Zidovudine weakens the virus early, while nevirapine

blocks its replication. Used together, they provide the best chance of

preventing transmission.

“These two drugs are administered during pregnancy,

delivery, and breastfeeding to ensure maximum protection for both the mother

and the baby,” he said.

“The mother receives zidovudine and nevirapine

as part of a combination therapy to reduce viral load, while the baby is also

given prophylactic doses to provide additional protection after birth,” Dr.

Maina added.

The combination is also crucial because of

the issue of drug resistance. Drug resistance occurs in two ways: through

improper use of drugs; if drugs are not taken as prescribed, at the right

dosage and frequency, it can lead to the development of resistant strains of

the virus. Moreover, individuals may already have drug-resistant strains in

their system, which can then be transmitted to others, including from mother to

child. Combination therapy is very critical, as it makes it harder for the

virus to develop resistance to all the drugs being used simultaneously.

Reasons for stockouts

Stockouts of antiretrovirals (ARVs) in Kenya are

not new. Procurement delays, funding gaps, and reliance on donor supply chains

have made the supply of HIV medication unpredictable.

Dr. Evans Mbuki, Head of Health Products and

Technologies at the National AIDS & STI Control Programme (NASCOP),

explains that sometimes stockouts happen because only one manufacturer bids

during procurement.

“If that manufacturer experiences delays, we

face shortages. Earlier in 2024, we ran out of ARV suspensions for newborns due

to a production issue.”

To mitigate the impact of stockouts, he

recommends redistribution of stock within counties as a crucial strategy to

address localised shortages.

“Counties should establish stock levels

and consumption patterns across facilities to ensure equitable

distribution," said Dr. Mbuki.

Kenya’s HIV treatment programme depends heavily

on donor funding, with the latest data showing 63.5% of funding coming from external

sources.

“For us to stop relying on donors, the

government must invest more in HIV services. Counties need to allocate budgets

for healthcare workers, clinics, and supply chain management. Without this

commitment, service delivery will be compromised when donor funds diminish, and

for long-term sustainability, we must invest in local drug manufacturing,” Dr.

Mbuki warned.

Dr. Mbuki also highlighted the importance of

integrating HIV services into general healthcare.

“HIV is a chronic ailment like any other. We

need to move away from standalone Comprehensive Care Clinics (CCCs). Clinicians

should manage HIV patients alongside other cases like diabetes or antenatal

care. This integration would optimise workforce use and improve service

quality.”

Crisis looms

As of early this year, Kenya’s HIV treatment

landscape faces another major threat: funding uncertainty.

Historically, the United States’ President's

Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) has been a cornerstone of Kenya’s HIV

programmes.

Over the last two

decades, PEPFAR contributed approximately $8 billion. However, changes in international aid policies

have made this funding less secure.

A recent executive order from U.S. President

Donald Trump initiated a reassessment of U.S. foreign aid, leading to a 90-day

freeze on funding, including PEPFAR support.

This sudden halt has thrown Kenya’s HIV

treatment plans into jeopardy.

The Ministry of Health, alongside the Council of

Governors and key health agencies, has projected that Kenya needs at least Sh28

billion annually to sustain its HIV programmes.

Currently, donor support covers only a fraction

of this, leaving a $78 million funding gap, a shortfall that could translate

into even more drug shortages.

“Despite our best efforts, domestic funding for

HIV remains below target,” says a Ministry of Health official. “Only 34% of the

required funding has been raised domestically, far below the 50% goal set under

the Kenya AIDS Strategic Framework.”

Cost of a broken system

For clinical officers like Mr. Mujera, the

hardest part of the job is breaking the news to a mother that her child has

tested HIV-positive.

“You feel like you’ve failed her,” he admits.

“At six weeks, when we do the DNA PCR test, we pray for a negative result. If

the baby is positive, it’s heartbreaking.”

And yet, there are victories.

“When an HIV-exposed infant tests negative at

two years old, we celebrate. We dress them in gowns and cut cakes; it’s a small

victory in a long battle.”

But how many more children will miss out on

these celebrations if funding and supply chain issues persist?

Way forward

Kenya is now scrambling for solutions. President William Ruto,

speaking at PEPFAR’s 20th anniversary in Kenya, acknowledged the programme’s impact:

“In 20 years, PEPFAR has channelled over $6.5

billion into Kenya’s HIV response. As a result, we have seen an 83% reduction in new

infections and a 65% drop in HIV-related mortality.”

Yet, the question remains how can Kenya sustain

these gains without guaranteed foreign aid?

Several countries have successfully transitioned

to alternative funding models:

- South

Africa has significantly

reduced donor dependency by at least 70% by allocating more of its

national budget to HIV treatment.

Kenya could follow suit by prioritising HIV care in its domestic budget.

- Rwanda has integrated HIV treatment into its national health

insurance scheme, making care accessible to all citizens. Kenya’s Social

Health Insurance Fund (SHIF) could be expanded to cover ARVs

comprehensively.

- Uganda

has

leveraged private sector partnerships, with companies funding HIV

programmes. Kenya’s corporate sector, including telecom giants

like Safaricom, could play a bigger

role in bridging the funding gap.

The Kenyan government

has already pledged $10 million for the Global Fund’s Seventh Replenishment, a 67% increase from its previous commitment.

But this is only a start.

Fight is not over

Despite the looming crisis, health workers like

Mr. Mujera remain determined.

“We cannot end HIV transmission while babies are

still being born positive,” he says. “Science exists. The drugs exist. Now we

just need a system that works.”

For mothers like Everlyne, that future cannot come soon enough.

This article was produced as part of the

Aftershocks Data Fellowship (22-23) with support from the Africa Women’s

Journalism Project (AWJP) in partnership with The ONE Campaign and the

International Center for Journalists (ICFJ).