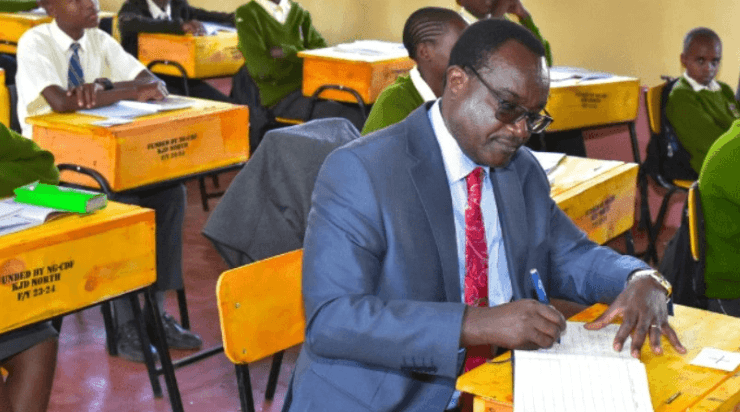

A victim of defilement in Nyali subcounty, Mombasa

/ BRIAN OTIENO

Some community health promoters could be sabotaging sexual and gender-based violence cases within Mombasa, the county government has said.

This could be deliberately or involuntarily, as some work in cahoots with perpetrators, while others lack adequate information on referral pathways.

“Not every community member knows about SGBV adequately. And remember information goes with resources,” Celina Kithinji, the Mombasa county sexual and gender-based violence, mental and adolescent health programme coordinator, said.

Other CHPs are also working silently with some civil society organisations, in a bid to increase the number of SGBV cases for purposes of donor funding.

“Again, we also have key actors in the community who have their own interests. So, people would be having information, but they want to divert the case. Instead of referring to the right place, they want to send to an organisation which is looking for data to build up their case for funding,” Kithinji told the Star on the phone.

There are also cases where community members are interested in protecting the perpetrator.

Some CHPs, she said, do not use the correct referral pathway, even though all subcounty hospitals can handle the cases faster and more conveniently.

“Most want to refer every case to Coast General whereas we have decentralised SGBV services. SGBV survivors can get services at the nearest health facilities,” Kithinji said.

In response to reports by some health promoters that Post Rape Care and P3 forms are only filled on Tuesdays and Thursdays at the CGTRH, making it difficult to collect evidence and help victims in time, the coordinator offered clarification.

The forms are available at all subcounty health facilities and can be filled by any licensed health practitioner, including doctors, nurses and clinical officers. Information from the PRC form is used to fill out the P3 form, she explained.

Challenges arise when police officers—for whatever reason—opt to transport patients to Coast General, even where the victim was attended to and obtained the PRC form at a different health facility.

“What we are advocating for is that we provide services within the areas where you are. This is cost-effective for the patient and convenient for follow-up,” Kithinji said.

There is also an information gap, as only half of community members know about SGBV and how such cases should be handled.

Kithinji stressed that the 72-hour window for SGBV victims to seek medical attention is crucial for both their health and for justice.

“The first point of contact should be the health facility. Why? Because the perpetrator might be HIV positive so once you reach the facility you are tested and given preventive measures so that you do not get infected. You will be followed up for five months,” she said.

Female victims are also given the Emergency Contraceptive Pill to prevent pregnancy.

Post-SGBV care is a comprehensive package: follow-up is done at the same facility and includes medication, surgical services if needed, psychosocial support like counselling and HIV testing.

But most survivors are not referred to health facilities within this critical period, which can scuttle positive outcomes.

“If this survivor does not reach a health facility within 72 hours, you lose most tangible evidence. So, even that court case may be weak, justice may not be found and you blame the judges, you will say police officers were bribed and the judiciary is corrupt.”

Evidence collected by the health department is crucial, as more than 80 per cent of positive outcomes in SGBV cases result from survivors getting timely health services.

She reiterated that apart from the referral hospital—which serves the entire Coast region—other facilities can offer services for SGBV cases, often faster.

Additionally, being a large referral hospital makes it impossible to have a doctor dedicated solely to the SGBV clinic. This is why form filling at the CGTRH is scheduled, even though doctors can be called upon when needed.

“A doctor is a person who will also be required to operate in theatre or see other special cases and will not sit just to wait for an SGBV survivor whose visit is not known,” she said.

“There are some facilities where the P3 form will be filled the same day that you are seen, especially these other lower facilities.”

Kithinji noted the need for more sensitisation among community members and CHPs, adding that the county is working to ensure these groups are better informed.

“We intend to train more CHPs so that they can have the correct information to provide and so that they can know it is not only Coast General that is providing Post-Rape Care services.”

Instant Analysis:

The 72-hour period after rape or defilement is often called a golden window because it is during this time that crucial evidence can be collected against the perpetrator. It is also when certain interventions are most effective in preventing negative health outcomes. A forensic medical examination, which collects evidence for potential legal proceedings, is most useful within this specific timeframe.