It’s a presidential function at Uhuru Park in 1982.

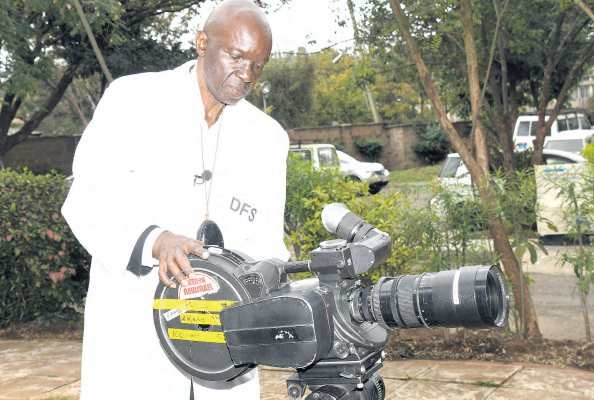

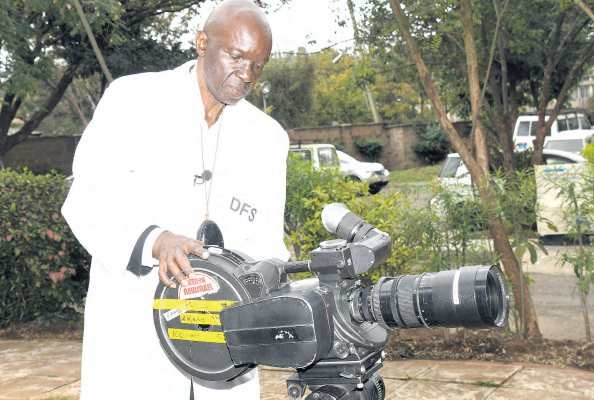

In the old days, you had to get it right first time to avoid wasting film.

Audio By Vocalize

It’s a presidential function at Uhuru Park in 1982.

Help us continue bringing you unbiased news, in-depth investigations, and diverse perspectives. Your subscription keeps our mission alive and empowers us to provide high-quality, trustworthy journalism. Join us today to make a difference!