When Kenyan educationist Mary Bengtsson, 59, got married to a Swede, she had a heartbreaking epiphany.

Her husband had souvenirs of his creations from way back when he was a toddler. Including a necklace on a teddy bear he got when he was just 18 months old. A violin with only one string. And his first toy car.

All these were the work of his hands under Sweden’s competency-based education (CBE). They were piled in a box and handed over when he finished school, and subsequently by his parents when he moved out.

“I saw this and I asked myself, ‘What do I have to show for being in school? I have nothing!’ It was so sad,” Bengtsson says.

“I find them (Swedes) taking pride (in their handicraft). ‘So this was your first toy car? Grandpa, look at mine!’ You see innovation.”

The mother of one grew up under Kenya’s post-Independence education system, 763. She regrets that her daughter, 36, who went through its successor, 844, equally has nothing to show for it.

But if Bengtsson was late to the party, she quickly caught up and became a master of CBE, both locally and abroad.

In Kenya, where CBE was rolled out in 2019, it is more commonly referred to by its syllabus, competency-based curriculum (CBC).

“CBE is the best system we could ever have,” she says. However, she admits the implementation could have been better.

“They did not allow all the stakeholders of education to be part of the decision and the walk, where now they say, okay now, I think we are ready,” she says.

“But we are in it, and there’s no going back. We should’ve done this earlier, but what can we do now to make it work? Because CBE has to work.”

TEACHING BACKGROUND

Born Mary Wairimu Kariuki, Bengtsson started her teaching career from the lowest level, P1, at Thogoto Teachers’ College in Kiambu county, where she did music.

A shortage of music teachers led the government to offer a crash course for P1 teachers, and Bengtsson seized the opportunity. She was then deployed to a school in Kirinyaga and then later to Kagumo High School in Nyeri, which she helped to get to the National Music Festival for the first time.

From there, she worked at the Braeburn Group of Schools for 12 years, before venturing abroad to the International English School in Sweden after more than 30 applications in Sweden and surrounding countries finally led to a response.

“And it was just the doing of God because for the eight years I was with them, I was the only African in that institution,” Bengtsson says.

She had to learn a new language and culture to fit in.

“I almost had my teaching certificate cancelled after four or five years just because of telling a student to stand at the back of the class and reflect on what they have said to me,” she recalls.

“That is child abuse. That is shaming the student in front of the others.”

Despite the culture shock, she rallied with the support of her husband and family, and went on to be nominated as the best teacher in Sweden for two consecutive years.

All in all, she has been a teacher for 30 years, lived in Sweden for 11 years and is now giving back by training teachers through a teacher-centric consultancy called Nimora. She launched it in 2020 and got clients in Sweden, Spain and Italy.

“Right now, I’m in international schools and private schools, and the sad part is that the ones who really need my help cannot afford me,” she says.

“I really hope that one day the government will appreciate that we have specialists in CBE who have worked in CBE in Europe for eight years, I have even developed a curriculum in Sweden for CBE. And I have seen it work.

“I wish there would be a programme, where it is like a county teachers’ programme put together, and the county pays for that and I facilitate.”

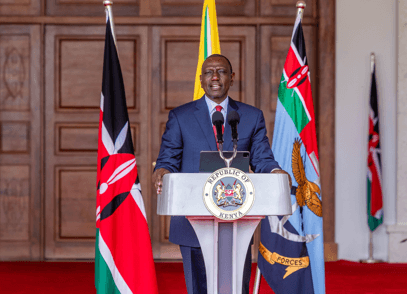

Bengtsson spoke to the Star features editor Tom Jalio while on a visit to Nairobi this month.

THE STAR: You say CBE is the best system. What makes it better than the other systems you have taught in?

MARY BENGTSSON: First of all, it’s hands-on, unlike the other systems, which were more of, how much do you know? CBE is what do you know and how can you apply that in real-life situations? 844 did not give us that.

Secondly, CBE is for everyone. 844 was more for those who were sharp, the A to C students. Not for those who could not even get a D, they’d get an E. It was also more for the white-collar jobs, someone who makes it well in class and becomes a doctor, teacher or pilot. But it did not mainly think of the skills, people who want to work with just skills. That electrician, that seamstress, and so on. CBE is holistic. It appreciates that we are all different. And so the way I approach something is not the same way you will approach it.

Thirdly, it gives an international approach. Once we do it here in Kenya and you move to another country, things might be different in terms of language and subject, but the approach is exactly the same.

Fourthly, there is equality when it comes to CBE because the international schools — AP, IB, IGCSE, A-Levels — they all use competency-based approach. So now when we come in as the Kenyan government and we bring in CBE, we are bringing equality. So that regardless of where you went to school, whether government or international school, you are all in the competency approach-based system.

Parents complain that they are asked to buy things every other day, over and above paying school fees. Is that not expensive?

It is very relative when you say it is expensive. Because here you are, you are able to buy your child something from Kenchic and other places. And when you are told to buy beads or something, you say it is expensive.

On the other hand, look at these beads. I came to know how to make the bracelets when I went to Sweden, when I was in my late 40s, because it was not introduced to me here.

So I disagree with the notion of expensive. Because they also don’t leave whatever they make in school. They take them home. And when that boy or girl gets married one day, they will have something to show their children.

Parents also complain that they end up doing homework for their children. Is that not a burden? And does the child really learn from that?

They are supposed to co-create. Some parents have a disconnect with their children. When the child does something, the parent is like, “Is that my daughter?” When will you ever know them? When they’ve brought work home, you don’t have time to sit with them, and 844 was not asking for that.

But now, taking even 15 minutes with your daughter is creating a bond between you and your child. So that even when they grow up, because of this bonding, they will not find it difficult to tell you about personal problems. ‘If we worked this out with Daddy when I was young, even this we can work it out together.’

Teachers complain they were not adequately prepared. What was missing? And how are you assisting?

CBE wasn’t given enough time for teachers to digest it, to change their mindset and to accept it.

Unlike with 844, where they went to colleges and were taught how to approach the methodology, they don’t know how to be a teacher in a CBE system. And so they are very unsure, and when you are unsure of something, you fight it.

They need to go through refresher courses, continuous professional development, where they meet with specialists and they point out this is what we are going through, and then they are given a starting point.

And then the specialist meets them again after two months and asks them, how did it go? Slowly by slowly and it will work.

So, equip the teacher, I cannot say that strongly enough. Empower the teacher.

I’m helping by creating awareness of what CBE is and the advantages of this system compared to 844. I am also helping them, the few schools I’m able to work with, to break down their content into smaller units, because that is what CBE is all about. I am mentoring them also and coaching them on what it means to be a CBE teacher. 844 was a teacher-driven system. The teacher says we keep left, and we keep left. CBE is a learner-centred approach, where as a teacher, you present what the students are going to learn, and then the student has a right to choose.

During the last elections, some politicians threatened to discontinue CBC if they won. What do you make of that?Thank God they didn’t win. Politics and education should not go together. We are gambling with our children’s lives. Politics can go with other things, but education, leave it to the experts, who will do enough research on what is right or not, what is working, what is not working and how to make it work.

While CBE champions individual competencies, a recent study by Education News found teachers in rural schools still conducting group tests, among other practices of 844. What is your take on that?

It’s not just in rural areas. I’ve been to a few schools and you look at the approach, and I’m like, what is happening here?

With exams, it’s the mindset. The ones in the rural schools, as they walk in the villages, they want that finger being pointed. “You see that Mwalimu, he is actually the one who all the students…” That’s what they want.

But how can you be in school for four years, and then you do one exam and it determines who you are? Continuous assessment is what portrays who we are. And that is what CBE advocates for (evaluating a learner’s skills and competencies through methods like portfolios, presentations and practical demonstrations, instead of exams).

What value does music and performing arts add to education?

I didn’t do music in primary or in high school. But when I went to Thogoto Teachers’ College, there was this young music teacher, Mr Bukenya, who would come with a lot of energy and say, “Hi, guys!” And we’d have a lot of fun. And I said, I want to be that kind of a teacher. That’s how I started music.

I thank God for my parents because my mother was a teacher and my dad was in education also, and they were very supportive. When I told Dad to buy me a guitar and he got me one, I remember my uncle coming and saying, “Ooh, now Wairimu will be the mugithi singer? So now you, you’ll be going to the bars and…”

And that really hurt me. But later on, I realised, to him that is what is music. But I sat Dad down and showed him, “Dad, you can write music.” I wrote music for my church.

Actually, one of my accolades is that I have written a hymnbook used by the ACK. I have translated it to notation, music notes. So that whoever comes, wherever they come from, even from England, they can actually sing that melody though they don’t know Kikuyu. So I started showing Dad that and he said, “Ooh, okay, this is it, eh?” So he believed in me and he pushed me.

Creative arts can transform and empower discipline. And it also makes those who were not academically very up there actually shine. It gives them an opportunity to redeem themselves, that although I’m not an A material, here, this is what I’m able to do.

And let’s face it, today, who is making more money, the A students or the creatives?

![[PHOTOS] Ole Ntutu’s son weds in stylish red-themed wedding](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn.radioafrica.digital%2Fimage%2F2025%2F11%2Ff0a5154e-67fd-4594-9d5d-6196bf96ed79.jpeg&w=3840&q=100)