His ascension to the papacy heralded many firsts.

Francis was the first Pope from the Americas or the Southern Hemisphere. Not since Syrian-born Gregory III died in 741 had there been a non-European Bishop of Rome.

He was also the first Jesuit to be elected to the throne of St Peter - Jesuits were historically looked on with suspicion by Rome.

His predecessor, Benedict XVI, was the first Pope to retire voluntarily in almost 600 years and for almost a decade the Vatican Gardens hosted two popes.

Many Catholics had assumed the new pontiff would be a younger man - but Cardinal Bergoglio of Argentina was already in his seventies when he became Pope in 2013.

He had presented himself as a compromise candidate: appealing to conservatives with orthodox views on sexual matters while attracting the reformers with his liberal stance on social justice.

It was hoped his unorthodox background would help rejuvenate the Vatican and reinvigorate its holy mission.

But within the Vatican bureaucracy some of Francis's attempts at reform met with resistance and his predecessor, who died in 2022, remained popular among traditionalists.

Determined to be different

From the moment of his election, Francis indicated he would do things differently. He received his cardinals informally and standing - rather than seated on the papal throne.

On 13 March 2013, Pope Francis emerged on the balcony overlooking St Peter's Square.

Clad simply in white, he bore a new name which paid homage to St Francis of Assisi, the 13th Century preacher and animal lover.

He was determined to favour humility over pomp and grandeur. He shunned the papal limousine and insisted on sharing the bus taking other cardinals home.

The new Pope set a moral mission for the 1.2 billion-strong flock. "Oh, how I would like a poor Church, and for the poor," he remarked.

His last act as head of the Catholic Church was to appear on Easter Sunday on the balcony of St Peter's Square, waving at thousands of worshippers after weeks in hospital with double pneumonia.

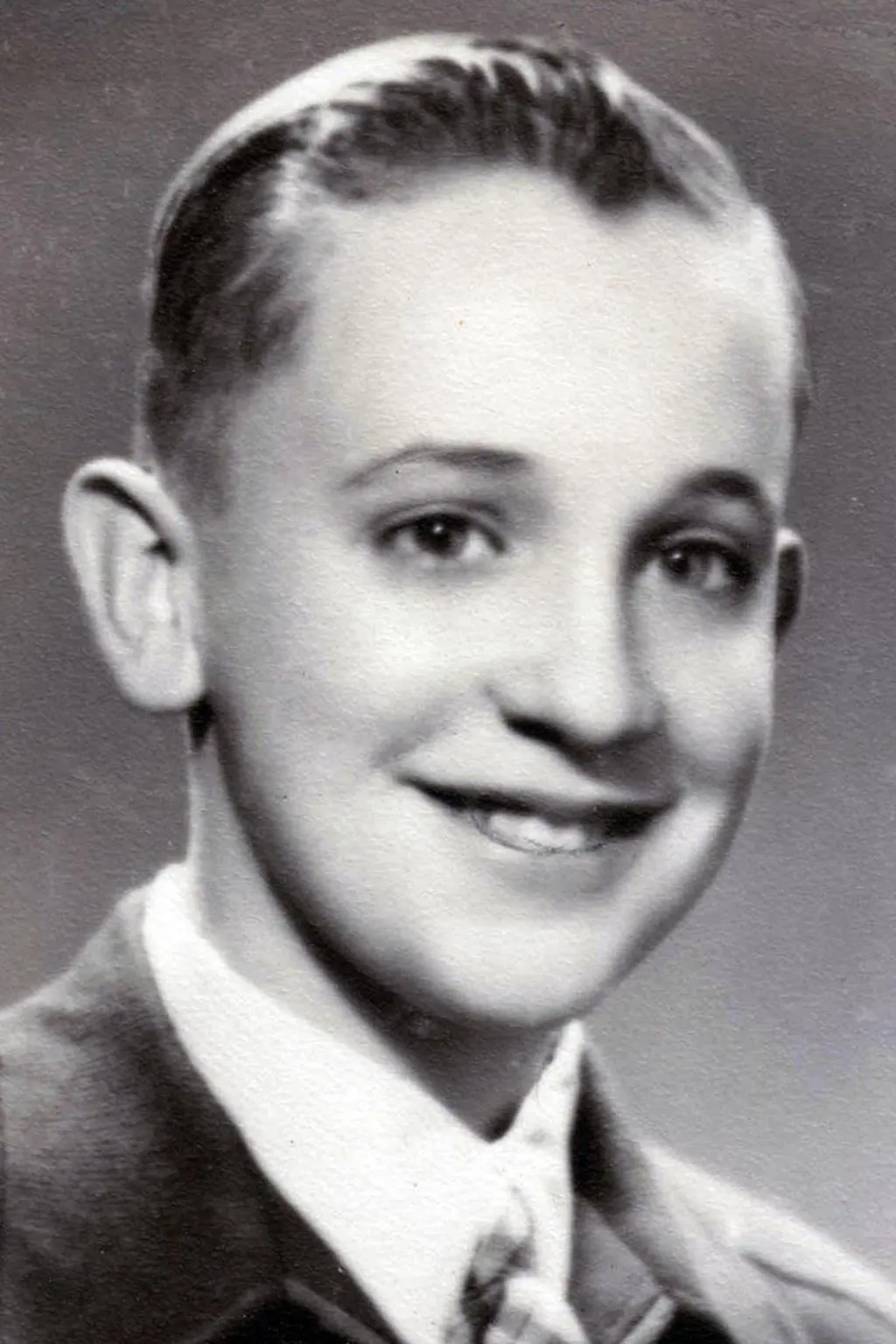

Jorge Mario Bergoglio was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on 17 December 1936 - the eldest of five children. His parents had fled their native Italy to escape the evils of fascism.

He enjoyed tango dancing and became a supporter of his local football club, San Lorenzo.

He was lucky to escape with his life after an initial and serious bout of pneumonia, undergoing an operation to remove part of a lung. It would leave him susceptible to infection throughout his life.

As an elderly man he also suffered from pain in his right knee, which he described as a "physical humiliation".

The young Bergoglio worked as a nightclub bouncer and floor sweeper, before graduating as a chemist.

At a local factory, he worked closely with Esther Ballestrino, who campaigned against Argentina's military dictatorship. She was tortured, her body never found.

He became a Jesuit, studied philosophy and taught literature and psychology. Ordained a decade later, he won swift promotion, becoming provincial superior for Argentina in 1973.

Accusations

Some felt he failed to do enough to oppose the generals of Argentina's brutal military regime.

He was accused of involvement in the military kidnapping of two priests during Argentina's Dirty War, a period when thousands of people were tortured or killed, or disappeared, from 1976 to 1983.

The two priests were tortured but eventually found alive - heavily sedated and semi-naked.

Bergoglio faced charges of failing to inform the authorities that their work in poor neighbourhoods had been endorsed by the Church. This, if true, had abandoned them to the death squads. It was an accusation he flatly denied, insisting he had worked behind the scenes to free them.

Asked why he did not speak out, he reportedly said it was too difficult. In truth - at 36 years old - he found himself in a chaos that would have tried the most seasoned leader. He certainly helped many who tried to flee the country.

He also had differences with fellow Jesuits who believed Bergoglio lacked interest in liberation theology - that synthesis of Christian thought and Marxist sociology which sought to overthrow injustice. He, by contrast, preferred a gentler form of pastoral support.

At times, the relationship bordered on estrangement. When he sought initially to become Pope in 2005 some Jesuits breathed a sigh of relief.

A man of simple tastes

He was named Auxiliary Bishop of Buenos Aires in 1992 and then became Archbishop.

Pope John Paul II made him a cardinal in 2001 and he took up posts in the Church's civil service, the Curia.

He cultivated a reputation as a man of simple tastes, eschewing many of the trappings of a senior cleric. He usually flew economy and preferred to wear the black gown of a priest - rather than the red and purple of his new position.

In his sermons, he called for social inclusion and criticised governments that failed to pay attention to the poorest in society.

"We live in the most unequal part of the world," he said, "which has grown the most, yet reduced misery the least."

As Pope, he made great efforts to heal the thousand-year rift with the Eastern Orthodox Church. In recognition, for the first time since the Great Schism of 1054, the Patriarch of Constantinople attended the installation of a new Bishop of Rome.

Francis worked with Anglicans, Lutherans and Methodists and persuaded the Israeli and Palestinian presidents to join him to pray for peace.

After attacks by Muslim militants, he said it was not right to identify Islam with violence. "If I speak of Islamic violence, then I have to speak of Catholic violence too," he declared.

Politically, he allied himself with the Argentine government's claim on the Falklands, telling a service: "We come to pray for those who have fallen, sons of the homeland who set out to defend their mother, the homeland, to claim the country that is theirs."

And, as a Spanish-speaking Latin American, he provided a crucial service as mediator when the US government edged towards historic rapprochement with Cuba. It is difficult to imagine a European Pope playing such a critical diplomatic role.

Traditionalist

On many of the Church's teachings, Pope Francis was a traditionalist.

He was "as uncompromising as Pope John Paul II... on euthanasia, the death penalty, abortion, the right to life, human rights and the celibacy of priests", according to Monsignor Osvaldo Musto, who was at seminary with him.

He said the Church should welcome people regardless of their sexual orientation, but insisted gay adoption was a form of discrimination against children.

There were warm words in favour of some kind of same-sex unions for gay couples, but Francis did not favour calling it marriage. This, he said, would be "an attempt to destroy God's plan".

Shortly after becoming Pope in 2013, he took part in an anti-abortion march in Rome - calling for rights of the unborn "from the moment of conception".

He called on gynaecologists to invoke their consciences and sent a message to Ireland - as it held a referendum on the subject - begging people there to protect the vulnerable.

He resisted the ordination of women, declaring that Pope John Paul II had once and for all ruled out the possibility.

And, although he seemed at first to allow that contraception might be used to prevent disease, he praised Paul VI's teaching on the subject - which warned it might reduce women to instruments of male satisfaction.

In 2015, Pope Francis told an audience in the Philippines that contraception involved "the destruction of the family through the privation of children". It was not the absence of children itself that he saw as so damaging, but the wilful decision to avoid them.

Tackling child abuse

The greatest challenge to his papacy, however, came on two fronts: from those who accused him of failing to tackle child abuse and from conservative critics who felt that he was diluting the faith. In particular, they had in mind his moves to allow divorced and remarried Catholics to take Communion.

Conservatives also adopted the issue of child abuse as a weapon in their long-running campaign.

In August 2018, Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, a former Apostolic Nuncio to the US, published an 11-page declaration of war. He released a letter describing a series of warnings made to the Vatican about the behaviour of a former cardinal, Thomas McCarrick.

It was alleged that McCarrick had been a serial abuser who attacked both adults and minors. The Pope, Archbishop Viganò said, had made him a "trusted councillor" despite knowing he was deeply corrupted. The solution was clear, he said: Pope Francis should resign.

"These homosexual networks," the archbishop claimed, "act under the concealment of secrecy and lie with the power of octopus tentacles... and are strangling the entire Church."

The ensuing row threatened to engulf the Church. McCarrick was eventually defrocked in February 2019, after an investigation by the Vatican.

During the Covid pandemic, Francis cancelled his regular appearances in St Peter's Square - to prevent the virus circulating. In an important example of moral leadership, he also declared that being vaccinated was a universal obligation.

In 2022, he became the first Pope for more than a century to bury his predecessor - after Benedict's death at the age of 95.

By now, he had his own health problems - with several hospitalisations. But Francis was determined to continue with his efforts to promote global peace and inter-religious dialogue.

In 2023, he made a pilgrimage to South Sudan, pleading with the country's leaders to end conflict.

He appealed for an end to the "absurd and cruel war" in Ukraine, although he disappointed Ukrainians by appearing to swallow Russia's propaganda message of having been provoked into its invasion.

And a year later, he embarked on an ambitious four-country, two-continent odyssey; with stops in Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and Singapore.

In recent months, Francis had struggled with his health. In March 2025, he spent five weeks in hospital with pneumonia in both lungs.

Jorge Mario Bergoglio came to the throne of St Peter determined to change it.

There will be some who would have preferred a more liberal leader, and critics will point to his perceived weakness in confronting the institution's legacy of clerical sexual abuse.

But change it, he did.

He appointed more than 140 cardinals from non-European countries and bequeaths his successor a Church that is far more global in outlook than the one he inherited.

And, to set an example, he was the no-frills Pope who elected not to live in the Vatican's Apostolic Palace - complete with Sistine Chapel - but in the modern block next door (which Pope John Paul II had built as a guest house).

He believed anything else would be vanity. "Look at the peacock," he said, "it's beautiful if you look at it from the front. But if you look at it from behind, you discover the truth."

He also hoped he could shake up the institution itself, enhancing the Church's historic mission by cutting through internal strife, focusing on the poor and returning the Church to the people.

"We need to avoid the spiritual sickness of a Church that is wrapped up in its own world," he said shortly after his election.

"If I had to choose between a wounded Church that goes out on to the streets and a sick, withdrawn Church, I would choose the first."