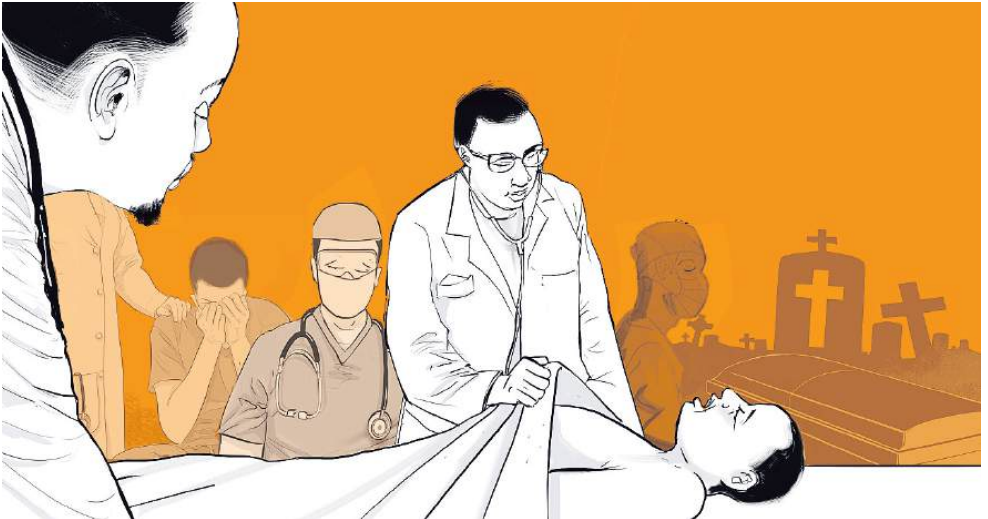

Last week, I fell seriously ill. Not just fatigued. Not mildly unwell. I was ill enough to fear for my life.

I had access—to care, to diagnostics, to some of the best surgical minds around me. I could ask the right questions, weigh the best options, and act fast. And still, I could have died.

And in the haze of fever, pain and uncertainty, one thought kept circling back: If I died today, how many others would die with me—not from my illness, but from the absence I would leave behind?

This isn’t ego. It’s not martyrdom. It’s math.

I am one of only a few orthopaedic oncologist in Kenya—a country of more than 55 million people. I see patients with aggressive bone and soft tissue tumors, often in advanced stages, whose lives hang in the balance of timing and surgical decision-making. If I am not available—because I’m in surgery, out of town, or fighting for my own life—there is no immediate replacement.

And so the truth is this: If I had died last week, others would have too.

Patients whose tumors would grow unchecked while awaiting referral. Children, whose limbs might have been saved, but weren’t. Mothers whose pain would be managed instead of treated. Lives lost not to cancer, but to the collapse that comes from over-relying on a single person in place of a system.

And that is what makes the health equity conversation so urgent—not in theory, but in the arithmetic of survival.

We often say healthcare systems are under strain. But that language is far too soft. We are past strain. We are now in a state of systemic precarity—where the absence of one provider, one voice, one clinic can mean the end of care for dozens. And that is neither fair nor sustainable.

Health equity is not charity. It’s not even access. It is infrastructure. It is the promise that survival does not depend on luck, geography, or whether the one specialist in your disease category happens to be healthy that day.

But to build that kind of equity, we must do six hard things:

1. Acknowledge that health equity is political

This isn’t just about building clinics. It’s about shifting power and resources. It means acknowledging that the system was built to serve some better than others—and that real change will be uncomfortable.

2. Move beyond access to agency

I survived this past week because I didn’t just have access—I had agency. I could ask, choose and act. True equity gives patients that kind of control—not just a clinic to wait in.

3. Radically invest in the workforce

One orthopaedic oncologist for 55 million people is not a workforce issue. It’s a national emergency. We need proactive training programmes, incentives for service in underserved areas and systems that protect specialists from burnout and erasure.

4. Create financing models that don’t punish the poor for being sick

Out-of-pocket healthcare is a tax on misfortune. Health equity requires pooled risk, strategic subsidies and the treatment of healthcare as essential infrastructure, not as a luxury service.

5. Listen to patients—and track suffering

Hopelessness is not just emotional—it’s measurable. We need tools that identify suffering early: patient feedback systems, transport support, referral tracking. Quiet deaths should count in our data.

6. Decentralise excellence

It is not acceptable for all specialist care to be concentrated in capital cities. We must build regional centres, deploy telemedicine meaningfully and invest in modest but capable facilities across the country.

I did not die last week. But I came close enough to see the edge.

And what terrifies me more than my own mortality is knowing how many lives are tethered to mine in ways that should never happen in a functioning system. That is not a legacy. It is a failure of succession. And it is a warning.

Health equity is not about reducing my importance. It’s about ensuring that no one patient’s survival depends on one person ever again.

Okumu is a surgeon, writer and advocate of healthcare reform and leadership in Africa