We can complain all we want as Kenyan citizens when it comes to the Social Health Authority’s failures, but one thing we may not be acknowledging is our role in this failure.

In the dry season, when families in rural Kenya prepare evening meals, an elder will ask the younger children to fetch firewood. They return with individual sticks that snap easily in their hands.

The elder shakes his head, gathers the sticks and ties them into a bundle. He then hands the bundle back to the children and asks them to break it. They can’t. That is the lesson: “sticks in a bundle are unbreakable”. Unity creates strength; separated, we are brittle.

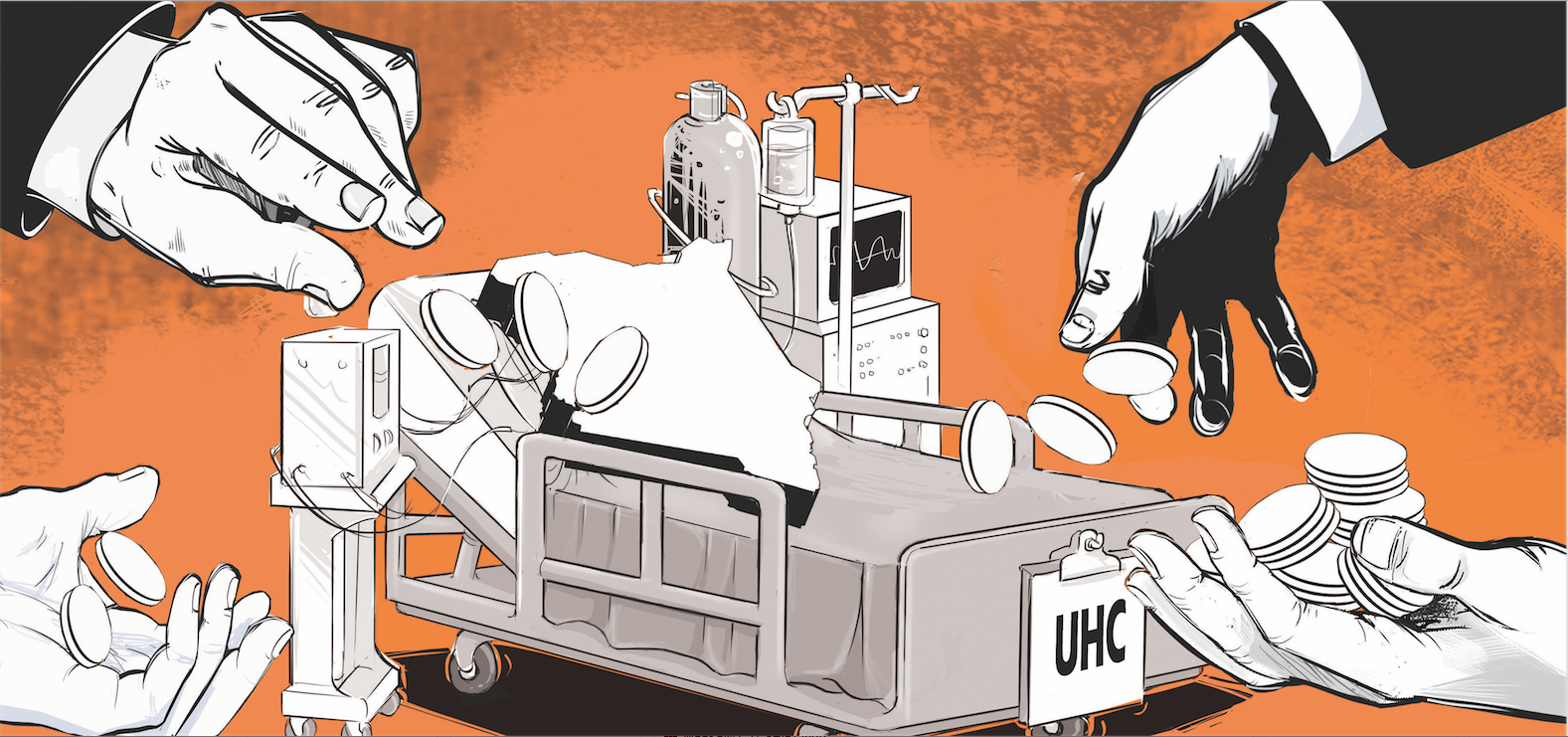

Universal health coverage is our generation’s bundle. It is a covenant, not between citizens and faceless bureaucrats, but among neighbours.

Every shilling you contribute today may not heal you tomorrow, but it may buy a caesarean section for the woman down the road or chemotherapy for a farmer’s child. When only those who are already ill join, the bundle falls apart; the fire goes out.

An old isiZulu proverb says, “hands wash each other”: by helping our neighbour, we help ourselves. Another African maxim declares, “a person is a person through people”.

These sayings express the spirit of Ubuntu — a philosophy Desmond Tutu describes as recognising that “you can't exist as a human being in isolation”. Our health scheme is not simply a government programme; it is the modern expression of these ancient truths.

Yet today our bundle is fraying. Kenya’s Social Health Authority has 25 million registered members, but only 4.5 million have completed the means test, and fewer than one million pay premiums regularly.

In July 2025, just over 70,000 salaried workers contributed Sh 5.9 billion, while 187,000 informal workers from a potential pool of 16.7 million gave Sh 780 million. Under the old NHIF, 1.8 million informal workers were enrolled; under SHA that number has halved. In other words, a tiny fraction of Kenyans are holding the bundle for everyone else.

Part of the problem is that the system feels arbitrary and punitive. Formal workers pay 2.75 per cent of their salaries, but for small traders and boda‑boda operators the means test makes little sense.

Many are told to pay Sh 6,000 a year — money that competes with school fees and food. The government promised monthly payments, but the portal often fails and instalments have been suspended without explanation.

In a country where incomes rise and fall with the rains, demanding a lump sum pushes people to wait until they need surgery to register, undermining the very principle of risk pooling.

Trust is further eroded by employer non‑compliance. Only 53,000 of 98,112 registered employers remit deductions on time; 44,000 firms owe Sh 4.7 billion.

Civil servants, whose premiums were deducted directly from their pay slips, were shocked to discover that the money never reached the SHA. Employers act as gatekeepers and when they default, workers are left uncovered.

Fraud and delayed reimbursements to hospitals also feed public cynicism. If you find out that your neighbour took your money and never delivered it to the common purse, why would you keep contributing?

Let us be honest: many of us do not agree with the way our government designed this system. I have reservations, and many experts have argued for alternative models. But the proverb “If you want to go fast, go alone; if you want to go far, go together” reminds us that no health scheme can succeed without solidarity.

We can either sabotage the current structure in hopes of forcing a better one, or we can claim it, demand reforms and make it work. Complaints alone will not build a hospital wing. Just as in a family, we sometimes work within imperfect arrangements because doing so serves a greater good.

Rebuilding the bundle requires lowering barriers to entry and restoring fairness. The complex means test should be scrapped or simplified into a self‑declaration. Contributions could be tiered, starting low, with flexible payment periods that reflect informal incomes.

Mobile money should make paying as easy as buying airtime. Benefits should reflect commitment: people could access basic services immediately but would receive full coverage only after a history of contributions to discourage last‑minute sign‑ups. Employers who fail to remit must face penalties and public naming to protect their workers.

Most importantly, we need to revive the cultural narratives that make health insurance a moral act. Public education campaigns should not only explain premiums and benefits; they should tell stories. When you pay every month and later see families like Margaret Wanjiku’s or Brian Kipchoge’s receiving lifesaving care, you feel the power of solidarity.

When people like James Mutua or Jane Mwikali pay and are denied services, trust crumbles. Churches, mosques and women’s groups should lead discussions on risk pooling, as our ancestors taught, Umoja ni nguvu; utengano ni udhaifu. As Tutu said, Ubuntu means knowing “you belong in a greater whole” and are “diminished when others are humiliated or diminished”. Health insurance is a way of affirming our shared humanity.

Universal health coverage will only succeed if we see ourselves not as passive recipients but as co‑architects. Government must keep its promises, providers must bill ethically, and citizens must contribute consistently. When one of us fails, all of us lose. When we act together, our contributions become unbreakable. So let us gather our sticks, tie them tightly, and light a fire that warms every home.

Okumu is a Surgeon, writer and advocate of healthcare reform and leadership in Africa