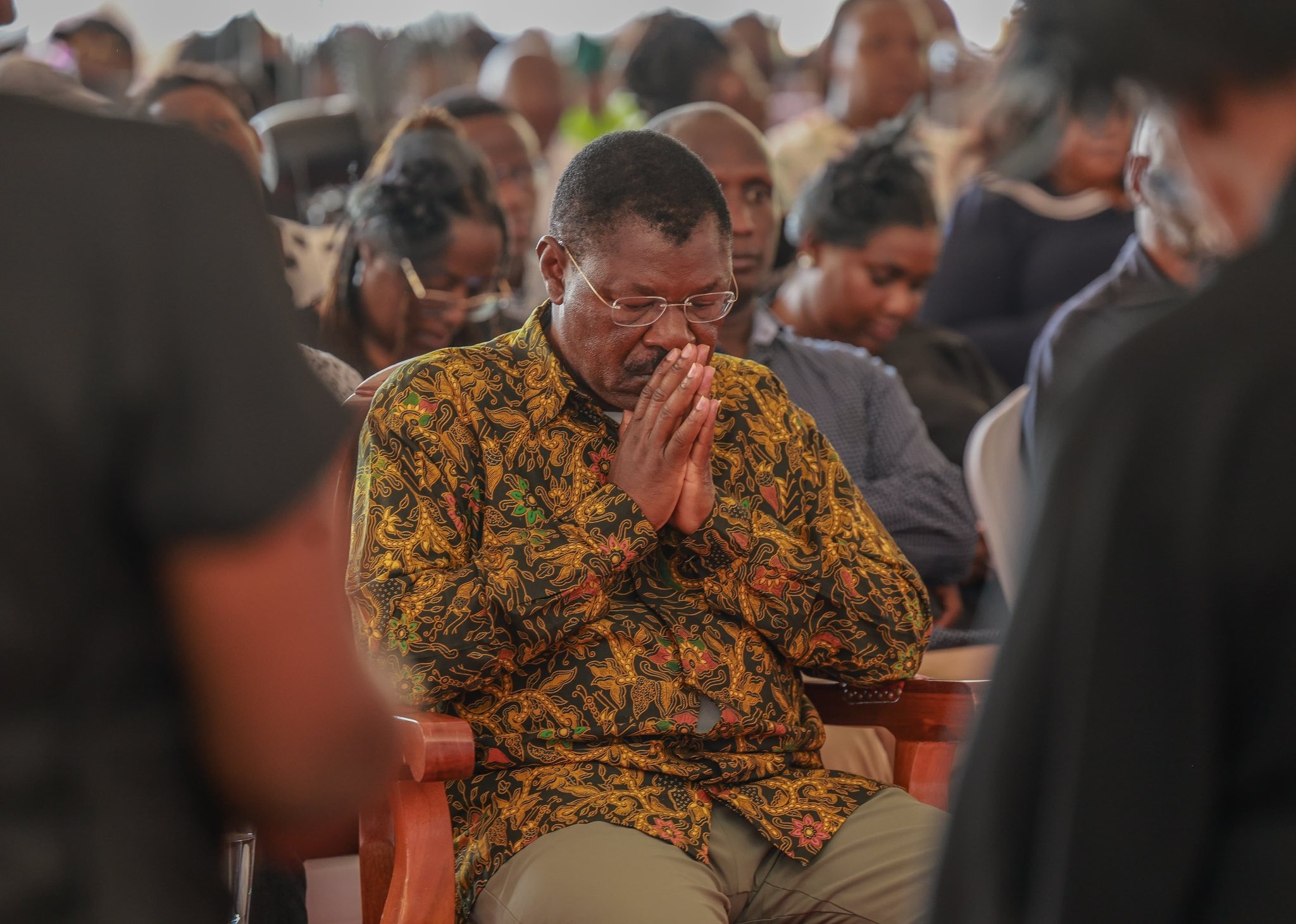

MOSES NYABUTO

MOSES NYABUTOSocial protection in Kenya has long been viewed as a financial lifeline and a safety net for the elderly, the poor, Persons Living with Disabilities (PLWDs), orphans and vulnerable children.

However, in Kenya, a country where malnutrition still haunts millions of households, it is time to rethink social protection as more than a patch for poverty but as a tool for promoting healthy and dignified lives, starting with better nutrition.

A recent study commissioned by the Catalyzing Strengthened policy Action for healthy Diets and Resilience (CASCADE) project, implemented by Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) and CARE Kenya examined how our social protection policies link, or fail-to-link with food and nutrition outcomes across county levels.

The findings, covering Nairobi, Nakuru and Nyandarua counties, tell a powerful story; there are policies in place with great potential, but patchy implementation and poor coordination limit their impact.

Social protection as a right

Kenya’s Constitution (Article 43) states that; - every Kenyan has a right to social security, food, and the highest attainable standard of health.

The Kenya Social Protection Policy-2023 (KSPP-2023) and other strategies like Vision 2030, the Kenya Nutrition Action Plan, and the Agriculture Sector Transformation and Growth Strategy outline an ambitious vision for inclusive development.

On the ground though, reality is often different. Taking for example, Inua Jamii, is the flagship cash transfer programme which supports orphans and vulnerable children, older persons, and people with severe disabilities.

However, while cash transfers improve purchasing power, they do not necessarily guarantee nutritious diets. Nutrition counseling is rare while food prices are constantly high. Many counties lack accompanying programmes to guide or reinforce better dietary choices.

The missed nutrition opportunity

In the agriculture sector, there is investment towards productivity and input subsidies.

However, the investment towards diet diversity is insufficient. While households may grow more, this does not necessarily always mean they feed better.

For instance, in some regions known for high milk production, many families often sell most of their milk for income, leaving little for household consumption and dietary needs.

In education, Kenya’s school meals programmes have shown immense promise in tackling hunger and keeping children in school. However, budget cuts, inconsistent coverage, and a lack of local ownership threaten sustainability.

While regulations exist that promote lactation stations and healthy food options at workplaces, enforcement is weak, especially in the informal sector and value chains where most Kenyans work.

All of this points to the fact that the country is missing the nutrition opportunity in social protection.

Sealing the gaps

This, however, is not about starting from scratch. It is about integrating what the country already has to ensure the existing gaps are well sealed. Cash transfer programmes for example, could include “cash plus” approaches-pairing funds with nutrition education or food vouchers.

Agriculture subsidies could prioritise biofortified crops or protein-rich foods. With Kenya’s health workforce on the ground for nutrition screening and counselling, Community Health Promoters (CHPs) referral systems can further be integrated to social protection systems to automatically link vulnerable households to available social safety nets.

Nutrition-related conversations must be all inclusive, bringing in all genders and cutting across demographics. Often, food decisions are seen as a women’s issue, ignoring the household power dynamics that influence what ends up on the plate.

Most critically, resources must be invested where there is value. Currently, Kenya allocates just 0.4 per cent of GDP to social protection.

This is way below the 3.3 per cent recommended by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) for middle-income countries. Without financial muscle, even the best policies just gather dust.

Counties also have the opportunity to bridge this financing gap by passing county-specific social protection laws and allocating additional budgets to complement national efforts.

Nutrition is foundational, not a luxury. A well-fed population is healthier, more productive, and more resilient to economic and environmental or climatic shocks. If

Kenya truly wants to invest in its human capital, social protection is the way for her citizenry to thrive, not just survive.

Moses Nyabuto is a social protection officer, GAIN, Kenya