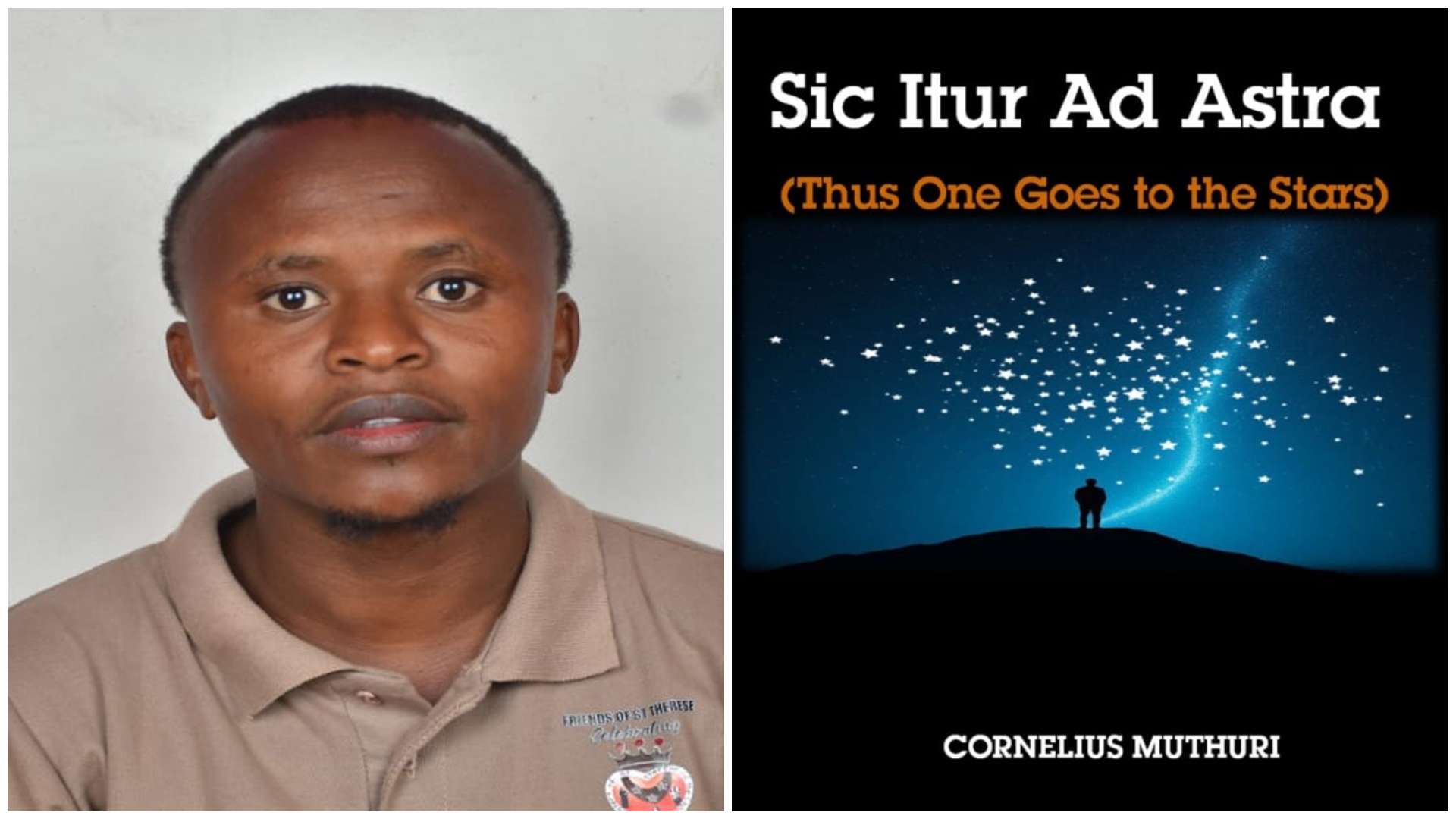

This week, he launched his second book of poems at the Alliance Françoise to critical acclaim. The book is curiously titled in Latin: Sic itur ad astra (Thus one goes to the stars).

It brings together 30 captivating poems, which have a foreword from the avid scribe Alfred Nyamwange as a precursor.

The new offering presents itself as a collection of verses and a cartography of ascent: spiritual, aesthetic, psychic.

The opening poem, ‘A Black Lion’s Cub’, sets the tone with an almost Blakean audacity, infantile birth imagined as a cosmic revelation. Here, the poet does not so much enter the world as erupt into it, claiming: “The venom of the spitting cobra / was my syrup in sickness” (Muthuri 2025, p1).

The line startles with its potent mixture of beauty and menace, merging healing and harm, sustenance and poison. This is a dualism that recurs with ritual insistence throughout the volume.

One is reminded of the British poet TS Eliot’s Gerontion: “History has many cunning passages, contrived corridors / And issues, deceives with whispering ambitions”.

So, too, does Muthuri’s poetic voice seem caught in a world that heals as it wounds, remembers as it forgets, sanctifies as it desecrates.

Indeed, the anthology’s most persistent accomplishment is its unflinching mythologising of the self. We accost a self at once heroic and broken, personal and archetypal. Like Yeats’s “foul rag and bone shop of the heart,” Muthuri offers us the detritus of experience not as lamentation but as sacrament. He lifts the banal into the symbolic, the wounded into the oracular.

Yet it is not all grandiloquent mythos. In “Poetry Is,” the poet shifts registers with disarming simplicity: “Poetry is like swimming; / you hold your breath to float / in a pool of imagination”.

Here, in the delicate liminality between metaphor and declaration, Muthuri gives us a miniature ars poetica.

The imagery, though gentle, is not without depth. To float is not to rise, but to suspend oneself between drowning and flying. Such is the poet’s task: not to escape the world, but to inhabit it more fully, breath held, body trembling, afloat between utterance and silence.

In “I Rest in Peace,” however, the tone shifts toward tragic irony, culminating in a line that lands with devastating finality: “Cancer did not take my breath… / But the man I married in my teenage!” (Muthuri 2025, p41).

This is no rhetorical flourish. It is the brutal compression of narrative, of emotion, of time. The slow build-up of the poem, culminating in this final twist, echoes the notion of poetry of the English tradition of using of anticlimax as a revelation. This line contains decades of unspoken suffering, heartbreak not as a climax but as a condition.

And yet, not all is flawless. In ‘Strength of a Man’, Muthuri addresses gendered expectations with a clarity that borders on percolative didacticism: “A man without money is like the Messiah-cursed fig tree; / his wife harangues him every evening he returns without a cake in his hand” (Muthuri 2025, p5). The simile, though potent in its biblical echo, leans heavily on its polemic.

The critique of patriarchal economics is vital, but the method of delivery here lacks the ambiguity that poetry demands. In fact, the reader is not invited to discover the meaning but merely to receive it.

Where earlier, Muthuri allows symbols to do the work of argument, here, he risks reducing symbol to statement. In “Dialectism,” too, a promising metaphor of land scarred by civilisation becomes ensnared in a kind of linguistic sermon. One cannot help but wish for more obliquity, more shadow in the light.

Yet, perhaps these moments of didacticism are the necessary fissures in a work otherwise so tightly controlled. I see them as portals through which the reader glimpses not only the poet’s mind but his passion. Sic itur ad astra is, after all, a young work, and I do not mean in its immaturity but in its fervour, its readiness to overreach.

What is most thrilling, however, is the young poet’s recurrent juxtaposition of the sacred and the profane. In “Noli Me Tangere,” the gospel according to John is transposed into the sweat-and-stench reality of a butcher’s stall.

“I drool over your lips,” utters the butcher to a woman, a line so vulgar it shocks precisely because it follows the titular invocation of Christ’s words to Mary Magdalene (Muthuri 2025, p9).

Here, profanity becomes both desecration and transfiguration. Muthuri dares to imply that holiness is not lost in the marketplace, only more difficult to detect. His spiritual vision is not that of naïve piety. It is one of scorched devotion: a belief honed on the anvil of disillusionment.

There is something unmistakably magnetic in this new book. In it, the poet has crafted for us a world where love coexists with cruelty, where ancestral identity is both inheritance and burden, where faith is never uncomplicated but never entirely absent either. His poems do not comfort. They do not plead. They summon.

I read this book twice this week and it came to me as a cathedral of contradictions. Think of it as sermon in staccato that, though unfinished, is already echoing with hymns of strange beauty.

The book is available from leading bookstores and from the publisher and the poet at: https://elongopublishers.co.ke; [email protected]