According to the Cambridge Dictionary, a euphemism is “a word or phrase used to avoid saying an unpleasant or offensive word”.

That is to say, it is the linguistic equivalent of wrapping a brick in cotton before hurling it through someone’s window. They still get hit with the brick, but at least you showed consideration in trying to soften the blow.

This fondness for verbal sugar-coating is not new. Shakespeare himself was a serial euphemiser. He adored turning the rude and the deadly into something that could be safely smuggled past the prim and proper.

His famous phrase “the beast with two backs” in Othello is a euphemism for sex, a description that sounds at once majestic and mildly zoological.

Likewise, when Lady Macbeth says King Duncan “must be provided for”, she does not mean she is ordering him a nice casserole. She means murder is on the menu.

It was a clever trick: audiences who enjoyed bawdy innuendo got their wink-wink fun, while more delicate theatre-goers could pretend it was all terribly sophisticated.

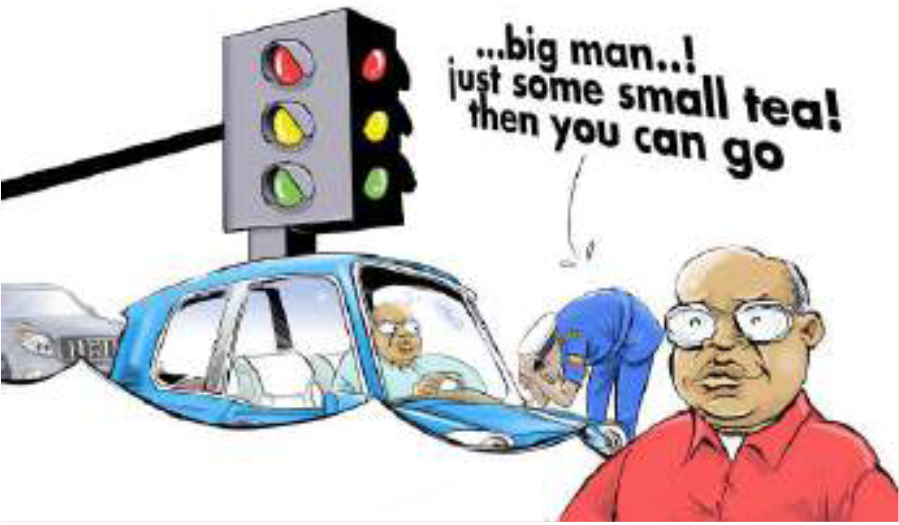

The tradition continues across the globe, though often with a financial twist. In South Africa, for example, a bribe is politely dressed up as “cool drink money”. The implication is that the traffic officer is thirsty, rather than corrupt.

In Kenya, one might offer “chai ya wazee” (tea for the elders), which sounds charmingly cultural until you realise it is essentially paying someone not to arrest you.

Somewhere between a light refreshment and outright graft, these phrases ensure corruption is served with a side of linguistic hospitality.

Modern English is equally inventive. Nobody dies anymore; they “pass away”. Or, if we are feeling breezy, they “kick the bucket”.

People are never poor, merely “financially challenged”. Old age becomes “senior citizenship” and prisons have been rebranded as “correctional facilities”, as though they were summer camps where naughty people go to learn to sew.

Companies no longer fire employees; they “let them go”, as if releasing small birds into the sky. Entire departments vanish under the banners of “downsizing” or “early retirement”, phrases that sound like wellness retreats rather than unemployment queues.

In the domestic sphere, euphemisms multiply like rabbits. Menstruation is coyly referred to as “time of the month”, a phrase that makes it sound like a lunar festival rather than a biological reality.

Weight is another favourite playground. Nobody is fat, merely “big-boned”, which suggests a rare medical condition involving giant skeletons.

Divorce has been given a glamorous facelift as “conscious uncoupling”, a phrase so extremely delicate and light it could double as a new yoga pose.

Meanwhile, when one feels ill, one is “under the weather”, as if rain clouds are to blame rather than a dodgy mutura from the street vendor outside the local pub.

Euphemisms are particularly beloved in politics and war, where honesty tends to cause riots. Civilians killed in bombing raids are labelled “collateral damage”.

Torture becomes “enhanced interrogation”, which sounds suspiciously like a new feature on your phone. The trick is to smother horror in bureaucratic jargon so the public imagines paperwork instead of blood. It is proof that words do not merely describe reality; they disguise it, repackage it and occasionally chloroform it until it stops struggling.

What makes euphemisms enduringly funny is how transparent they are. Everyone knows “financially challenged” means broke. Everyone knows “let go” means fired. Everyone knows Aunt Flo’s “monthly visit” is not a family reunion.

Yet we cling to these phrases because they take the sting out of human messiness. Life is brutal enough without having to say so out loud.

In the end, euphemisms are humanity’s greatest party trick. They allow us to talk about death, sex, corruption, war, poverty, illness and divorce without clearing the room.

They soften, cushion and protect our fragile ears. Likewise, they also remind us that language is not just about information; it is about comfort, too.

So the next time you hear that a colleague has been “downsized”, that your neighbour has “kicked the bucket” or that a traffic cop is desperately thirsty for a “cold drink”, remember: It is not the truth being told, but the truth wearing a silly hat.