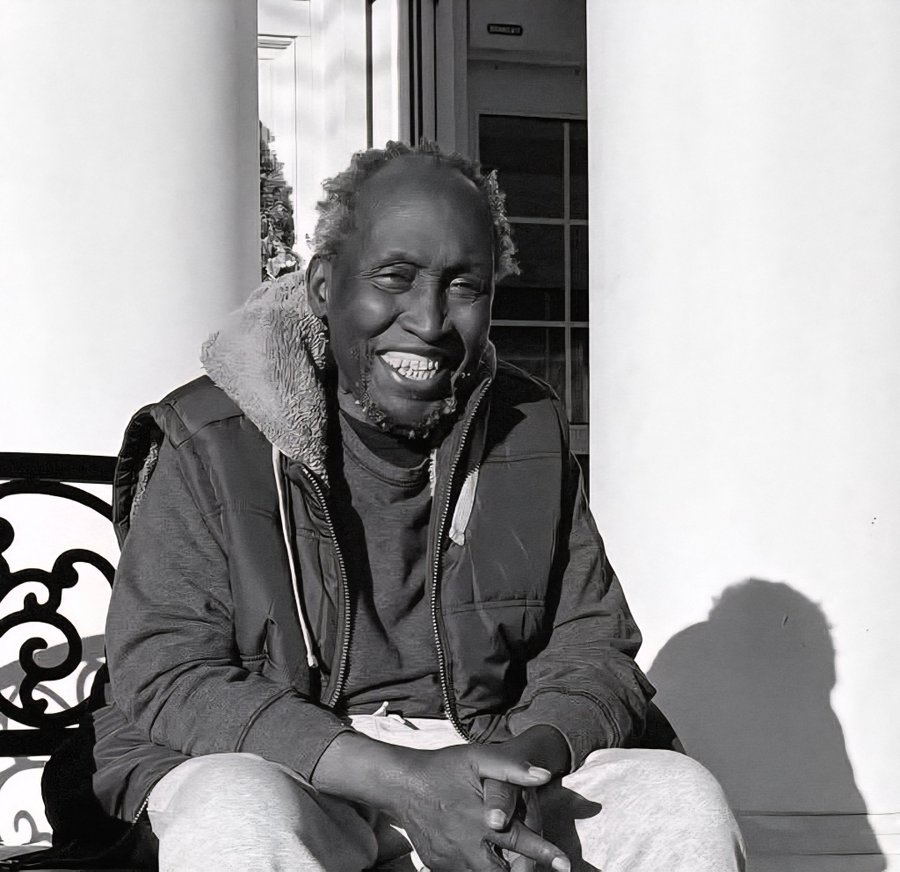

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, the towering Kenyan author, playwright, and post-colonial theorist, passed away on May 28, 2025, at the age of 87.

Recognised globally for his powerful political voice and literary innovations, Ngũgĩ dedicated his life to championing African languages, culture, and liberation through his extensive works.

His death marks the end of an era in the African literary community and beyond.

Early life

Born James Ngugi in 1938 in Kamiriithu, near Limuru, Kenya, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o entered a world defined by British colonial rule.

His upbringing unfolded within a large Kikuyu family, deeply influenced by the tumultuous Mau Mau Uprising, which spanned from 1952 to 1962.

This period of intense conflict was not merely a historical backdrop; it profoundly shaped his formative years and future literary endeavours.

The Mau Mau War of Independence left an indelible mark on Ngũgĩ's personal life.

He witnessed immense suffering within his own family: two of his brothers were killed, and his mother endured torture. His family home was razed to the ground, and another brother, involved in the insurgency, was captured by British forces and sent to a concentration camp.

These deeply traumatic experiences directly fuelled his critique of colonialism and the injustices it wrought.

His early novels, such as Weep Not, Child and The River Between, became authentic and impactful reflections of Kenyan history, drawing directly from his life.

Ngũgĩ pursued his education at Alliance High School before enrolling at Makerere University College in Uganda, then a campus of London University.

It was at Makerere that his literary journey began to flourish.

He published his first short stories and staged his debut play, The Black Hermit, at the 1962 African Writers Conference.

He later continued his studies at the University of Leeds in England, though he departed before completing his thesis on Caribbean literature.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o was previously married to Nyambura wa Ngũgĩ, his first wife, who passed away before him.

Together, they had several children, many of whom have also become notable authors and thinkers, including Tee Ngũgĩ, Mũkoma wa Ngũgĩ, Nducu wa Ngũgũ, and Wanjiku wa Ngũgũ.

He was later married to Njeeri wa Ngũgĩ.

Literary Beginnings

Ngũgĩ’s early literary output included novels like Weep Not, Child (1964) and The River Between (1965), which were initially published under his birth name, James Ngugi.

During his time studying in England, Ngũgĩ encountered the radical anti-colonial writings of figures such as Frantz Fanon. This exposure led him to embrace Marxist ideology, marking a significant political awakening.

This intellectual shift was evident in his subsequent works, including A Grain of Wheat (1967) and Petals of Blood (1977), which reflected his evolving political consciousness and foreshadowed a pivotal change in his linguistic approach to writing.

Upon his return to Kenya, Ngũgĩ began teaching at the University of Nairobi.

Here, his intellectual transformation translated into direct academic activism. He spearheaded a campaign to decolonise the curriculum, advocating for the prioritisation of African literature and languages over European classics.

His efforts were instrumental in the abolition of the English Literature Department, leading to its replacement with a broader, African-centred literary program.

In 1976, Ngũgĩ co-founded the Kamiriithu Community Education and Cultural Centre, a groundbreaking initiative where he collaborated with local communities to develop participatory theatre in Gĩkũyũ, his mother tongue.

This grassroots cultural work, alongside his published novel Petals of Blood (1977), contained strong political messages that the Kenyan government viewed as a direct threat.

This perceived threat led to Ngũgĩ’s arrest and imprisonment without trial in Kamiti Maximum Security Prison in 1977.

While incarcerated, he made the decision to abandon English as his primary language for creative writing.

He committed himself entirely to writing in Gĩkũyũ, even penning the first modern novel in the language, Caitaani mũtharaba-Inĩ (Devil on the Cross), on prison-issued toilet paper.

This commitment was further articulated in his highly influential non-fiction work, Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature (1986), where he argued that African writers must express themselves in native languages to effectively renounce lingering colonial ties and cultivate an authentic African identity.

This deep understanding of language as a tool of both colonisation and liberation underpinned his practical actions, highlighting his comprehensive approach to cultural freedom.

Exile

Following his release from prison in December 1978, Ngũgĩ faced continued harassment and was not reinstated to his teaching position at the University of Nairobi.

The persistent political persecution compelled him and his family to go into self-imposed exile in 1982, a period that would last for 22 years.

In exile, he continued to disseminate his ideas to global audiences as he held prestigious academic posts in the UK, the US, and Germany, including positions at Yale, Bayreuth, Northwestern, and New York Universities.

He ultimately became a Distinguished Professor of Comparative Literature and English at the University of California, Irvine.

Ngũgĩ continued to write and publish his works, including his prison diary, Detained (1981), and the satirical novel Matigari.

He also actively worked with organisations such as the London-based Committee for the Release of Political Prisoners in Kenya from 1982 to 1998.

In 2004, Ngũgĩ returned to Kenya after more than two decades in exile.

However, his homecoming was tragically marred by a violent, politically charged attack on him and his second wife, Njeeri wa Ngũgĩ, in their Nairobi apartment.

Following this traumatic event, he returned to the United States.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s enduring legacy is defined by his unwavering commitment to linguistic justice, African identity, and political courage.

He is widely recognised as one of the pioneers of modern African literature, having paved the way for numerous other East African writers and established a distinct African literary voice.

His impact extends far beyond individual literary achievement, instigating a profound cultural and educational revolution across Africa.

Ngũgĩ founded and edited Mũtĩiri, a Gĩkũyũ-language journal, further cementing his dedication to indigenous languages.

His short story, The Upright Revolution: Or Why Humans Walk Upright, has been translated into over 100 languages, a testament to the global resonance of his ideas.